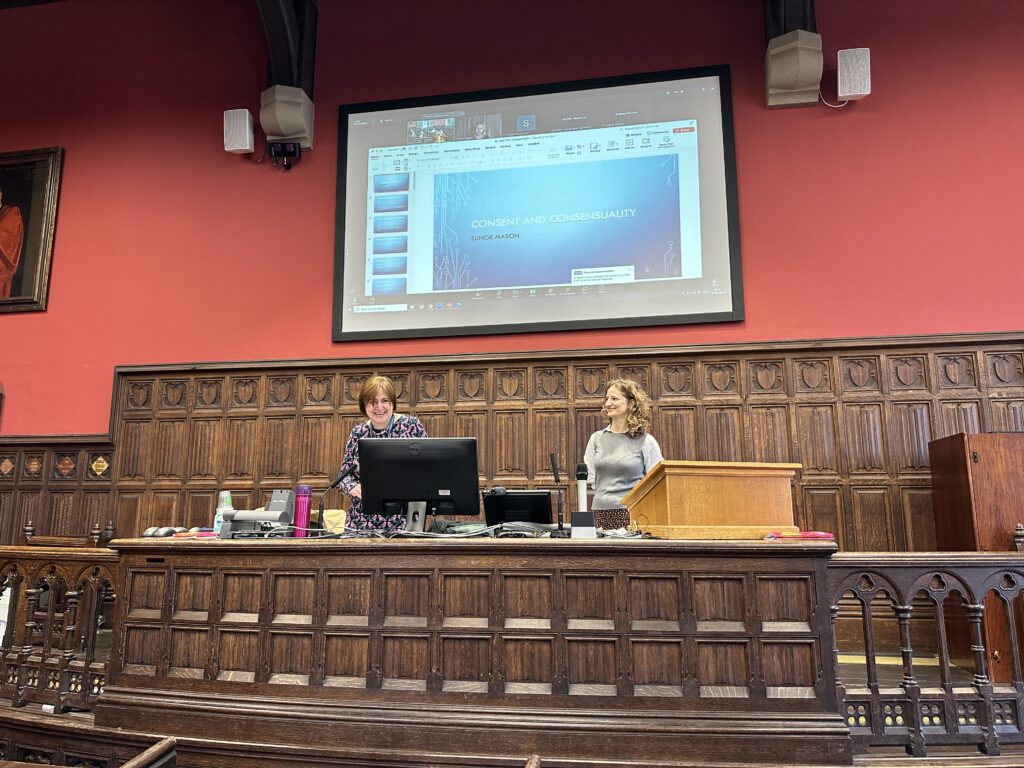

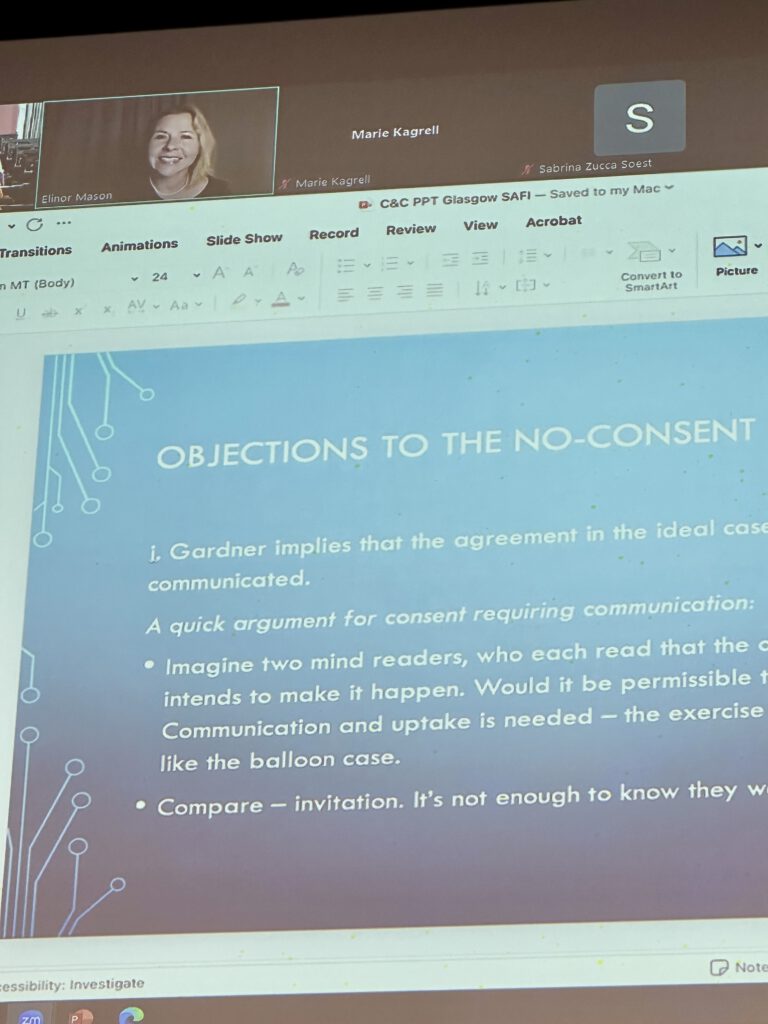

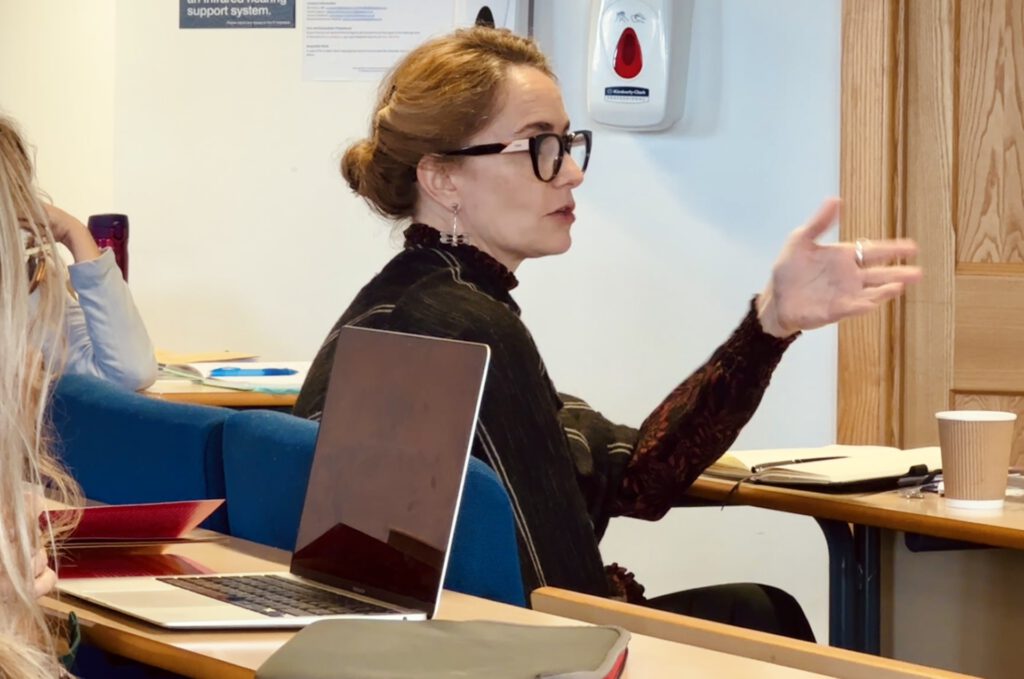

SAFI‘s 5th Annual Conference was held on the 10th, 11th and 12th of September 2024 at the University of Glasgow on the topic of ‘Consent’.

Consent is a central notion in legal and political philosophy, as well as in ethics and doctrinal law, ranging from the ideal of the consent of the governed to laws regulating sexual consent. The conference aims to explore the topic of consent, and connect related themes, topics, questions and issues, broadly conceived.

Our keynote speakers were Professor Elinor Mason (UC Santa Barbara) and Dr Camila Vergara (Essex). The conference was organized by Dr. Ana Cannilla and the team at the University of Glasgow.

Topic description

The idea of government by consent is an essential principle of constitutional morality. Arising as early as Plato’s Crito, it gained prominence in the seventeenth century with the writings of Hobbes and Locke, and features in landmark documents such as the US Declaration of Independence 1776 (“governments…deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed”) or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948 (article 21.3 “The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government”). In social contract theory, the role of consent is to ground the moral legitimacy of political authority. The argument is that when a state has the consent – express or tacit, real or hypothetical – of its people, it can legitimately demand obedience to its laws, and has a legitimate claim to the use of force when its laws are breached. It follows then that, under this view, political obligation – commonly defined as the moral duty to obey the law – is also grounded on the consent of legal subjects.

In constitutional theory, the consent of the governed underpins core principles of constitutional law such as the principle of parliamentary sovereignty, and shapes other relevant principles and doctrines in different ways, such as the rule of law, the separation of powers, and judicial review. Judges and legislators then rely on these to make decisions about allocation of power in disputes over institutional design (who gets do to what in constitutional government) and over individual rights (what is it that consenting majorities cannot take away from dissenting minorities). Moreover, constitutional decision-making processes such as referendums, constitutional arrangements such as devolution, and constitutional instruments such as sunset clauses bear on the normative appeal of the consent of the people. Similarly, recent debates about the relation between constitutionalism and populism have brought to the fore the question of the meaning, relevance and limitations of ‘the will of the people’.

If consent is relevant to questions of political philosophy and public law it is no less so because it is central to questions of ethics. It matters due to what Heidi Hurd called “the moral magic of consent”: by mere willing, consent turns permissible what would otherwise be impermissible. For instance, it makes entering into someone’s home a welcomed visit, instead of a rude invasion of property that could amount to unlawful trespassing. The constitutive nature of consent (whether it is a state of mind or requires a performance of will), its normative relevance (whether it can, in fact, be morally transformative), the values it may serve (such as autonomy, agency, or equality) or its conditions of validity (when does someone have capacity to consent, what limits may be imposed by third party’s interests) are issues subject to extensive debate in the legal theory and philosophy literatures.

Discussions on consent also take place within different areas of doctrinal law e.g. contract, medical, labour or family law, notably in the criminal law of sexual offences, and more recently in the area of law and technology. For instance, in post #MeToo times, conversations about what should count as valid consent to sex have come to the fore of public and scholarly agendas, together with reforms of criminal law and policy regulations in different countries. This comes on the heels of on-going feminist debates on the merits and perils of affirmative consent standards, on the harms of unwanted consensual sex, and on different approaches to sexualities. New technologies of artificial intelligence, such as deepfakes, bring further complications to our normative understandings and applications of consent and the principles and laws that regulate it. And in contract law, old debates about the balancing of autonomy or consent with fairness or efficiency is gaining new attention in light of the meteoric rise of standard form contracting and the increased use of contracts in the design of governance mechanisms beyond privity.

The conference addressed questions including, but not limited to;

- How should we best conceive of consent as an individual’s normative power?

- What are the different values that consent serves in its different applications to different areas of the law?

- How relevant is consent, how much does it matter for questions about rights and duties in private and public law?

- Are there any paradoxes of consent, for instance those critically identified in theories of social contract, that might also arise in applications of consent in ethics and private law?

- What is the relation between consent and alienation in labour law?

- What can be learnt from a comparative analysis of sexual assault laws and affirmative consent standards to improve ongoing reforms in criminal law and sexual violence campus policies around the world?

- Are regulators expecting the notion of consent to do more work than it can do?

- How is the ideal of the consent of the governed shaping our current constitutional orders?

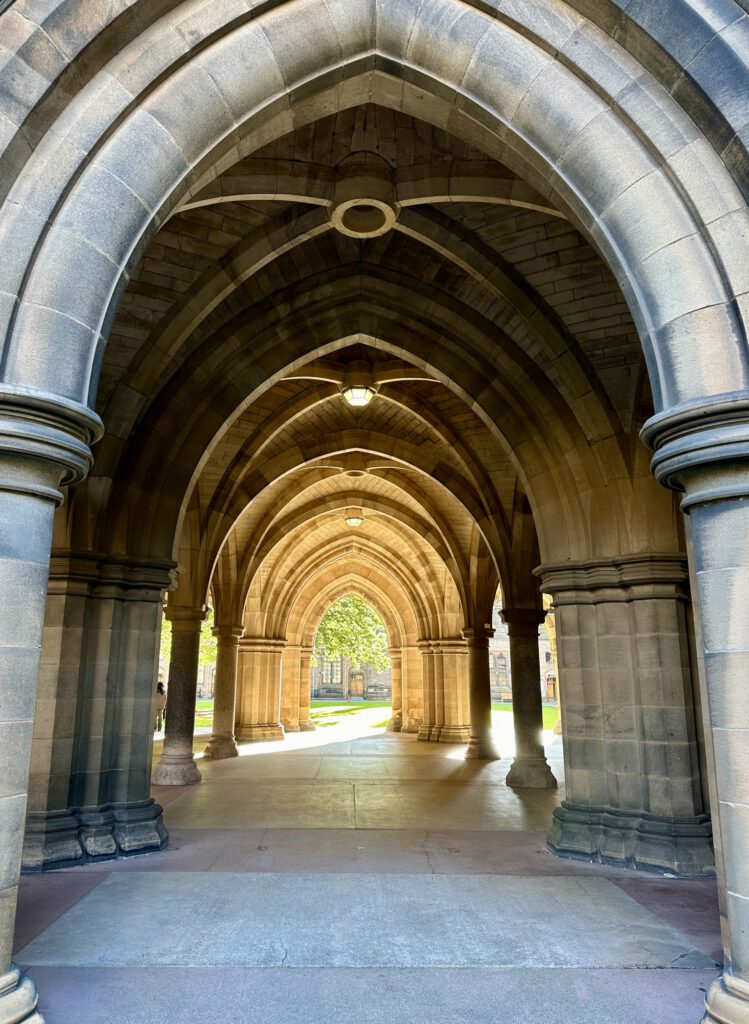

Programme and location

Impressions

Acknowledgements

This event is generously supported by the Scots Philosophical Association, the Society for Applied Philosophy, the University of Glasgow Chancellor´s Fund and School of Law.